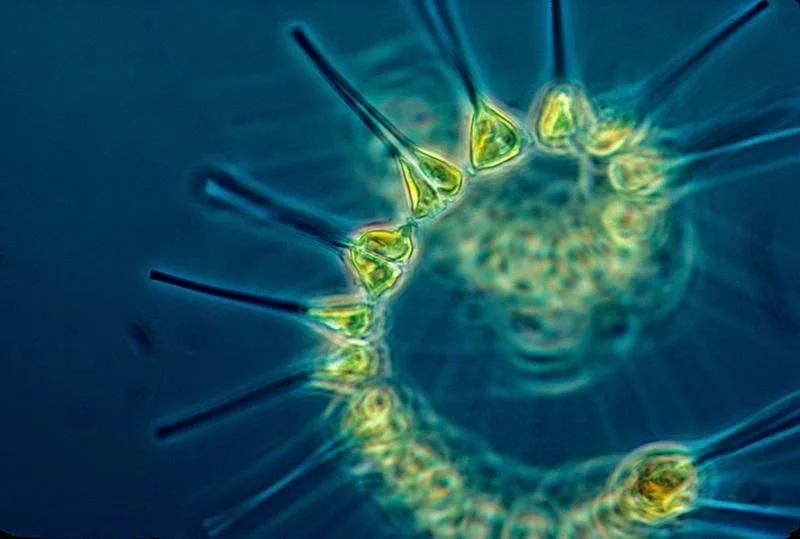

Phytoplankton are perhaps the most important group of organisms on our planet. They are microscopic, single-celled galaxies that come in many different shapes and sizes.

They are the movers and shakers of our marine ecosystems that transfer energy into food webs. Without them, there would be no krill, fish, penguins, seals or albatrosses.

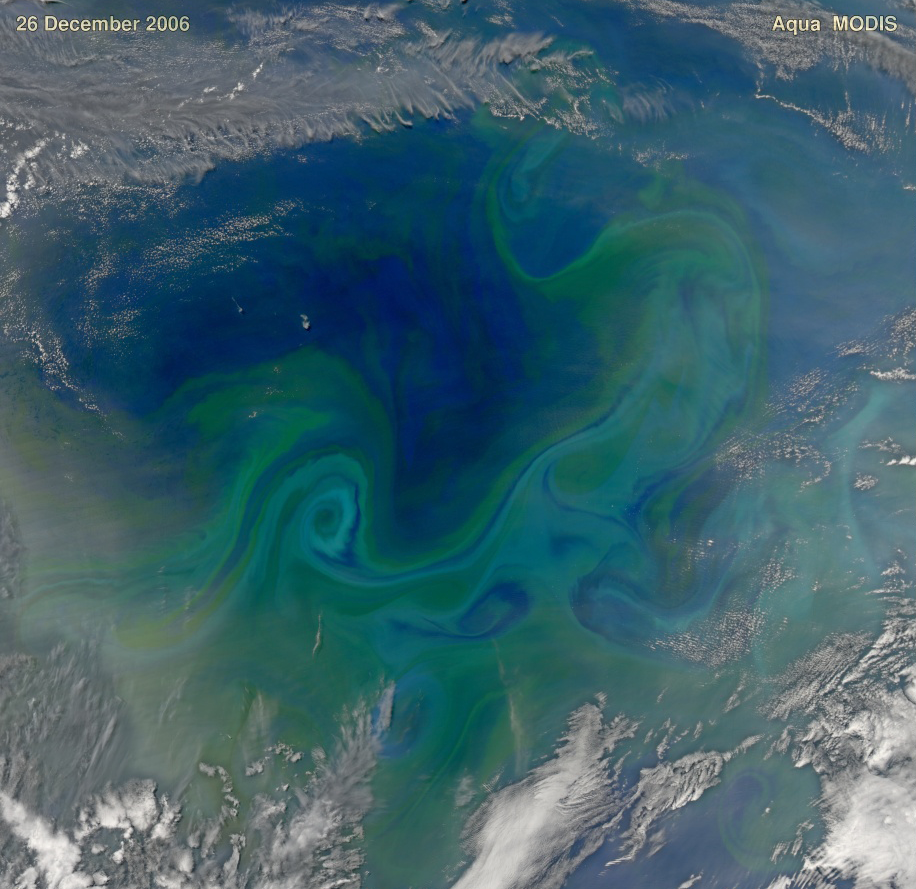

Basically, phytoplankton use nutrients from the water and, together with sunshine, create energy (via photosynthesis) that enables them to grow and multiply. When conditions are just right, phytoplankton are capable of erupting into enormous blooms. Below is a satellite image of a phytoplankton bloom associated with upwelling along the edge of a meso-scale eddy north of South Georgia:

The focus of my PhD is all about understanding the at-sea movements of two penguin species from Marion Island (the larger of the Prince Edward Islands). Because these penguins feed on krill, and krill feed on phytoplankton, penguins are largely dependent on the availability of phytoplankton. It's therefore really important for me to know where and when phytoplankton congregate. Recent advances in technology now allow people like you and me to have access to such information via satellites. This is called 'remote sensing'. One way to measure phytoplankton concentration or productivity is to look at the chlorophyll-a data collected from such satellites. Chlorophyll-a occurs in all phytoplankton and is the primary photosynthetic pigment which enables them to make energy from sunlight. The concentration of chlorophyll-a therefore reflects the concentration of phytoplankton at the sea surface. Because phytoplankton need sunlight to photosynthesise, blooms are not as frequent in the Southern Ocean during winter:

During the cold, cloudy winter, macaroni and southern rockhopper penguins from Marion Island spend all day, every day at sea; sometimes travelling more than 2000 km from the island. There is very little phytoplankton production around the islands during this period but when November comes the waters around Marion Island, and elsewhere in the Southern Ocean, burst with life and the penguins follow suit. Take a look at the seasonal variation in chlorophyll-a in the South-West Indian Ocean sector of the Southern Ocean:

(NOTE: black dot is Marion Island, grey areas are cloud cover, and each image represents one month)

Did you see the concentrations of chlorophyll during the summer months? It's no surprise that this is when the penguins breed. During this time the insane energy demands of their chicks require penguin parents to head to sea to find krill nearly every day, and because they need to return so often, they can only travel short distances. This makes having a close food source essential to the survival of their chicks.

The seasonal dynamics of phytoplankton abundance and availability at the Prince Edward Islands are, however, still not well understood, and neither is the relationship between phytoplankton and krill. But as scientists ask more questions, and collect more data, so the mysteries of these dynamic ecosystems slowly unravel and provide a little more insight into the ways of this beautiful planet.