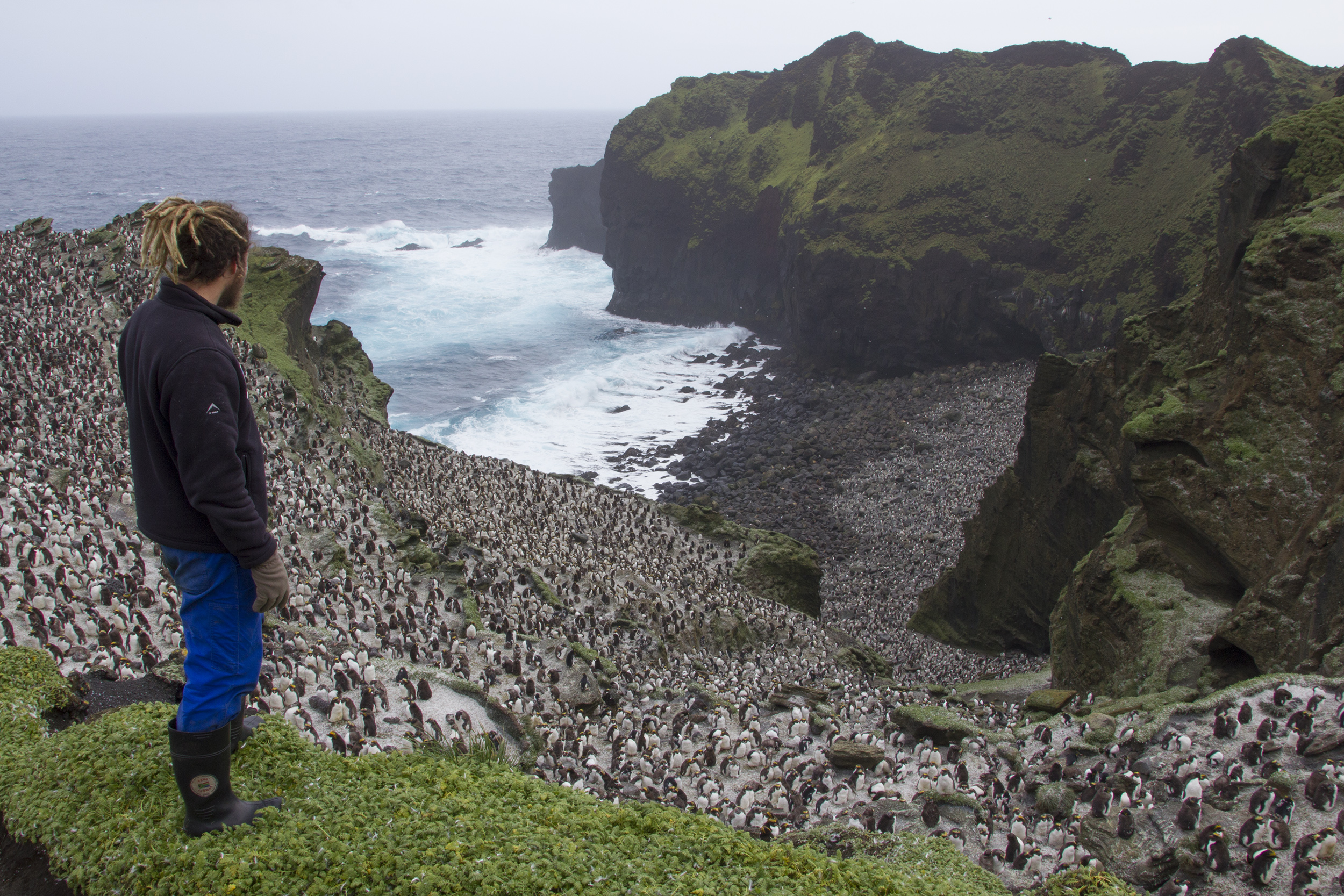

Every summer, approximately 300,000 macaroni and 80,000 rockhopper penguins return to the Prince Edward Islands to breed. During this period, their need to return regularly to the island to provision offspring constrains the distance they can travel to find resources. This makes them dependent on allochthonous prey i.e. originating from somewhere else.

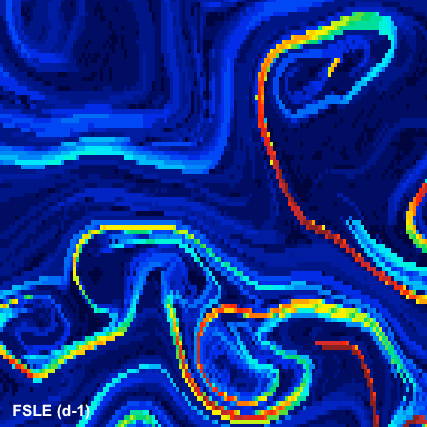

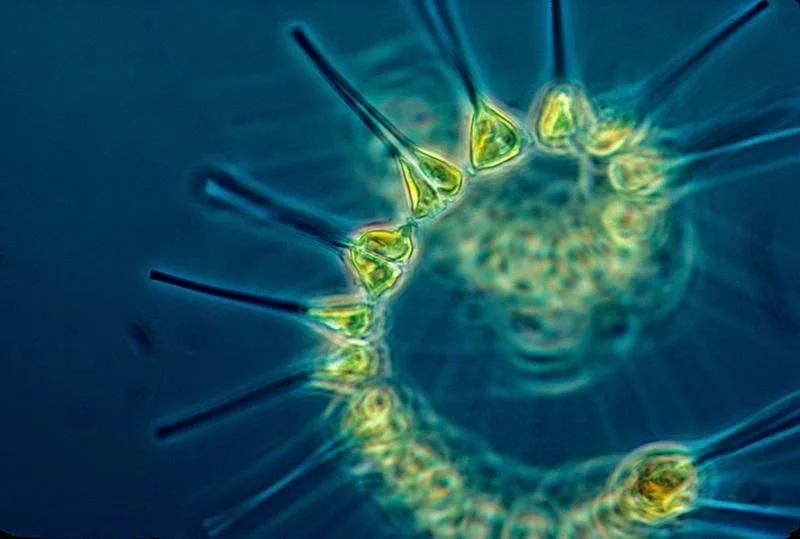

Macro- and mesoscale processes in the vicinity of the Prince Edward Islands are largely driven by fluctuations in the positions of the sub-Antarctic Front (SAF) and Antarctic Polar Front (APF). During years when the fronts are close to the islands, currents are stronger. During years when the fronts are farther away, currents are weaker. The proximity of the SAF and APF to the islands determines the composition of the zooplankton species. For example, when the SAF is closer to the islands, increased intrusions of warmer waters carry sub-tropical and sub-Antarctic species. Conversely, when the SAF is farther north, Antarctic species are more common. These processes influence the type of resources available to penguins during the breeding season.

The animation below represents daily maps of sea surface temperature anomalies. In 2011/12 and 2013/14, conditions were much warmer than in 2012/13. Note the positions of the fronts.

Interestingly, the dive depths of penguins were consistently to 40 to 60 m in 2011/12 and 2013/14, but during 2012/13, when cooler conditions persisted, dive depths were considerably deeper and penguins ate more fish. This highlights the role that the frontal systems play in delivering food to the Prince Edward Islands.