Phytoplankton are perhaps the most important group of organisms on our planet. They are microscopic, single-celled galaxies that come in many different shapes and sizes...

Viewing entries tagged

penguin

Phytoplankton are perhaps the most important group of organisms on our planet. They are microscopic, single-celled galaxies that come in many different shapes and sizes...

In February I decided to try my luck and I entered a few images into the prestigious Veolia Wildlife Photographer of the Year competition. I didn't expect much as the standard is very high, with professional photographers usually taking top honours. This year they received over 48,000 images from 98 countries so I was very surprised when I found out that three of mine had made it through to the final round of judging in May. Stoked!

The images that were selected aren't necessarily my favourites and this just highlights how subjective photography is. What constitutes a great image to one person is not necessarily a great image to another. That is probably the most beautiful thing about photography.

Here are my three images that made it through:

Category:

Creative visions

'This category is for conceptual pictures – original and surprising views of nature, whether figurative or abstract – which are judged purely on their artistic merits.'

Reflections of the Past and Present

Macaroni penguins

Eudyptes chrysolophus

are the largest avian consumers of marine resources in the Southern Ocean, but very often they themselves become the consumed. Life for a sub-Antarctic penguin is harsh. In the water they risk ending up in the menacing jaws of killer whales and fur seals, and on land they’re constantly harassed by skuas and giant petrels that rob them of their eggs and chicks and prey on the weak. As a researcher on Marion Island I got used to death really quickly because it was all around me; that’s just how the natural world revolves. Penguin colonies are littered with bones and many macaroni penguins even use them to build their nests. I tried to photograph the close relationship that macaroni penguins share with the dead but it always turned out too gruesome. I wanted to show it in a beautiful and subtle way.

The opportunity came on a wind-still and moody-skied day when I was walking along the edge of a colony and saw the reflections of passing penguins in a pond of bones; I knew it was perfect. The light was bad so I cranked up the ISO and narrowed the aperture to get a nice sharpness throughout the image. The macaronis stopped and stared at me across the pond scattered with the bony remnants of their past relatives. They soon gave up trying to figure me out and carried on up to their nests, most probably made up of some more bony remnants of past relatives.

Canon 550D + Sigma 18-200mm f/3.5-6.3 @ 1/80 sec, f/18, ISO 800

Category:

Animals in their environment

'Images must convey a feeling of the relationship between an animal and the place where it lives, and have a great sense of atmosphere.'

The Amphitheatre

Marion Island is home to more than 250,000 breeding pairs of macaroni penguins, nearly 13,000 of which spend the summer months building nests, mating, incubating eggs and raising chicks on a terraced landscape on the South-west coast called The Amphitheatre. It’s quite a sight to see the winding terraces, jam-packed with penguins, spiralling up to a point some 70 metres above the beach where they haul out. The acoustics are also fantastic! I’ll leave it up to your imagination to dream up what kind of sound emanates from thousands of buzzing macaroni penguins gathered in The Amphitheatre. Such a spectacle!

Canon 550D + Sigma 18-200mm f/3.5-6.3 @ 1/200 sec, f/11, ISO 400

Category:

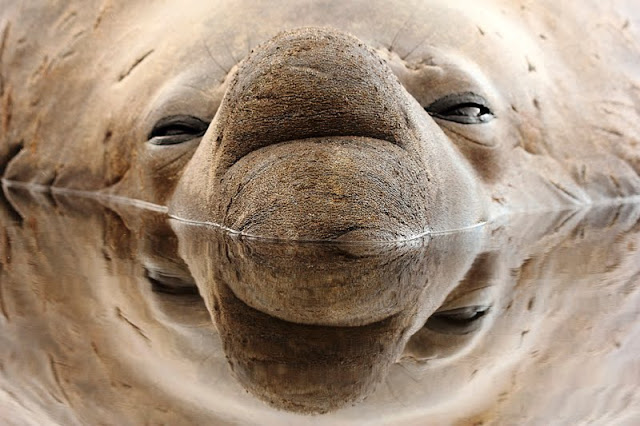

Animal Portraits

'A good portrait reveals something about its subject beyond the obvious. Images may be either close-up or mid-range and should convey a sense of intimacy, personality and spirit – the very essence of the animal – in a fresh and imaginative way.'

The Rebreather

Southern elephant seal bulls

Mirounga leonina

are notorious for their violent battles, roaring burps and large, elephant-like proboscises. In a species that is one of the most sexually dimorphic animals on the planet, it is this proboscis and their large body size which distinguishes the bulls from the females. The proboscis amplifies the sound of burps used to intimidate other bulls, as well as functioning as a sort of rebreather, reabsorbing moisture from the animals’ exhalations via specialised cavities. This reabsorption is important during the mating season when a bull needs to retain body moisture as he doesn’t leave the beach for an entire three months due to the constant threat of other bulls sneaking ashore and mating with his females.

The elephant seal bull photographed here was taking some time out in a rock pool when a friend and I stumbled upon him. The water was a perfect mirror and it looked so dreamy that we whipped out our cameras. His eyes then opened and he exhaled, shattering the mirror's surface with bubbling splashes and ricocheting ripples. He took a breath in and then under the water his trunk went. His eyes closed and his reflection in the water gradually returned. We took turns photographing him from a low perspective as he repeated his cycle, unfazed by our presence; breathe in, close eyes, sleep, open eyes, breathe out. We got our pictures, but one can't help but wonder why he didn't just sleep with his head on a nearby rock out of the water? Conserving body moisture I suppose.

Canon 550D + Canon 100mm f/2.8 @ 1/320 sec, f/4, ISO 200

Winners and highly commended images will be announced in mid-May. Check out the insane images from last year at the Natural History Museum's

.

As you may have guessed, the title is French, and manchot means penguin, but what does the word ‘penguin’ mean, and where does it come from? The intellect who gave me insight into this etymological mystery was the legendary David Attenborough. It was a dark, moody day and a light drizzle drifted playfully with the gusting squalls that moved alongside the cliffs. Every so often a stream of sunlight would break through the clouds and a rainbow would materialise over the wild seas. I was sitting next to my macaroni study colony and observing their ways whilst being audibly entertained by Sir David's intriguing stories. One particular story involved the now extinct Great Auk; a large flightless bird with a black back, white belly and upright posture, similar to the penguins we know today. Its distinctive features included a grooved bill, the sides of its neck and head were brown, and it had a large white patch in front of its eyes.

Like penguins, the Great Auk spent most of its year foraging at sea and returned to offshore islands in the Boreal summer to breed. As naval exploration began to radiate in the 16th and 17th centuries, encounters with these birds became increasingly common and by the beginning of the 19th century they had been hunted to extinction for their meat and feathers. During those times the Great Auk was known to sea-farers by another name - 'pengwyn'. It is of Celtic origin and when dissected composes of two welsh words; 'pen' meaning head and 'gwyn' meaning white. This may be an odd description for a bird whose head, apart from a white patch in front of the eyes, is predominantly brown or black, but there are further traits about the Great Auk which I have yet to mention. During the winter months these birds underwent a plumage change similar to that experienced by their relatives, the guillemot and the razorbill, in which their fore-neck, chin, and head feathers turned white. This must have made a significant impression on many a sailor, as the name spread throughout Europe.

When these sea-farers eventually ventured further South and encountered similar birds on sub-Antarctic Islands, the name 'pengwyn' was copied and pasted into log books and journals. Interestingly, over the ages the name stuck for those tuxedo-clad birds in the South, whereas those in the North were reclassified as auks, puffins, guillemots and razorbills. In some languages, the remnant of the Northern Hemisphere's 'pengwyn' still lingers in the French and Spanish words for Great Auk, which are 'Grand Pingouin' and 'Gran Pinguino', respectively.

Two hundred years after the extinction of the 'pengwyn' I've found myself amongst four species of their etymological descendents. Marion island is home to the king penguin Aptenodytes patagonicus, the gentoo penguin Pygoscelis papua, the macaroni penguin Eudyptes chrysolophus, and the southern rockhopper penguin Eudyptes chrysocome filholi. Regarding my MSc, I came to Marion to collect data on the foraging ecology and diving behaviour of the latter two, the crested penguins. Eudyptes is derived from Greek and means 'good diver', and chrysolophus and chrysocome mean 'with a golden crest' and 'with golden hair', respectively.

9th December:

"... My summer days at Funk have begun with a bang. Each sunny day tweaks my smile a little further up my cheeks and today is no exception. The kings are trumpeting on the beach, some incubating and some parading up and down in pairs. The maccie colony is radiating brays and testosterone; the males are incubating whilst the females are foraging at sea. I'm waiting for their eggs to hatch and for my three logger birds to return so I can oooh and aaah at their magnificent tracks and deep dives. The sky is a deep blue and the wind is calm; there's a little swell wrapping round from the South and the two-foot waves are clean and clear; a perfect day at the beach."

Over the past few summer months I've spent a vast amount of time at Funk Bay, my macaroni study colony, as well as at my rockhopper study colony near Whalebird Point, equipping birds with GPSs and TDRs and sitting, waiting, wishing for them to return. The GPSs record position (if they're at the surface) at a programmed interval and the TDRs record temperature and pressure, which in turn equates to depth and is used to analyse their diving behaviour.

Macaroni and rockhopper penguins live very similar lives. The only difference is that the rockhoppers arrive at Marion Island two to three weeks later than the macaronis. As a result, their breeding cycles differ by the same margin, which could be to reduce interspecific competition for resources.

The breeding, or chick-rearing, season of each species is divided into two stages; the brood-guard and the creche stage. During the brood-guard stage the female does all the foraging at sea whilst the male remains in the colony to brood/guard the chick, feeding only on his fat reserves. When the female returns from her foraging trip she takes over from the male and regurgitates a meal of krill for her little chick.

The brood-guard stage usually ends after 20-24 days, after which the chick is able to fend for itself. The chicks then stand together in creches while both parents head off into the deep blue to forage.

11th December:

"... I wanted to observe some nest dynamics so I marked a female that was on a chick by smearing strawberry jam on her back (I had run out of provitas to smear it onto). Later on I noticed that her partner was on the chick and that she had disappeared. I then saw her hopping down through the colony from the waterfall pond where she must have had a little drink of fresh water (as they surprisingly do). She and her partner had a greeting dance (flippers back, necks extended, heads up and waving from side to side whilst braying away) then hopped down to the beach where she waded through the loafers and the kings, and dived into the sea. I saw her porpoise a few times; she was heading ESE."

28th December:

"... So tired! Woke up at 04:00 to head down to Funkytown to see whether any of the loggers I deployed on the 26th were back. Beautiful sunrise but no logger birds around. I reckon they're taking longer foraging trips because their chicks are getting larger and can thus go longer without food. Central Foraging Theory predicts that birds will forage as closest to the island as possible, so if they encounter prey they will catch it. However, because of the large concentration of penguins diving for food there is a massive consumption of resources, and so the waters nearest to the island become depleted across the season. This may force them to travel further and take longer foraging trips to search for well stocked waters."

30th December:

"... The maccie chicks are so cute. They're really big now and are even standing next to their parents, sometimes looking like they're just about to fall over... They look as if they're trying so hard to be mature when they preen themselves, mimicking their parents."

After 60-70 days of life, the chicks eventually lose their fluffy down, whereafter they head to sea for the rest of the year until returning for the next summer's madness. At the same time, the parents, now with no responsibilities, head to sea for two weeks to indulge themselves and fatten up for their one month long moulting period which they will spend on land developing a slick new set of feathers.

Before I came to Marion these creatures were but a fairytale to me, only to be seen on BBC Wildlife documentaries and in my dreams. I've since had the opportunity to watch them build their nests, mate and nurture their eggs. I've watched them peck at each other furiously as well as prune and snuggle. I've watched as a shell broke open and a little chick let out its first chirps. I've watched parents come home from a hard day's work at sea and greet their partners with a brilliant display, shouting to the rooftops, before saying a little hello to their chicks and giving them a meal. I've watched the same little chicks grow and stumble around in all their cuteness, and I've watched an unlucky few get carried away in the beak of a skua. I've watched them lose their down and become penguins, penguins that will someday nurture their own eggs and feed their own chicks. I've watched, and I've experienced, and that is something I am truly grateful for, and will never forget.

"Kings are like stars. They rise and they set, they have the worship of the world, but no repose."

- Percy Bysshe Shelley

It's a Sunday at Kildalkey Bay and there's a cool, crisp breeze curling in from the ocean as the waves lap languidly at the shore. The ebb and flow of a benign continuum? It must be. I watch and listen, hypnotised, as cobbles are swept down and out, and up and over each other in a tranquil monotony, joined every so often by a few returning kings.

The salty air swirls through me in a wonderful way, invigorating a sense of nostalgia. The sun sits in the sky to the west, smiling large, as the penguins fill the air with a bustling cacophony of whistles and trumpets. It's a packed day at the beach and I'm staring straight into their lives, trying to understand.

Life as a king penguin is rather harsh. They’re continually exposed to wind, rain, snow and ice pellets and the only form of shelter is to huddle together. Individuals spend days and sometimes weeks at sea diving to great depths in search of squid and lantern fish, whilst trying to avoid the menacing jaws of killer whales and seals.

On land they’re a bit safer, but not completely. Giant petrels often storm into the colonies with their wings spread wide looking for weak or injured individuals and vulnerable chicks. The penguins scatter in fright and try to maintain a safe distance, which can sometimes lead to interesting patterns in the colony.

King penguins are asynchronous breeders, which means they don’t follow the same breeding cycles, and at Marion Island they lay eggs anytime between November and March. Whilst one parent heads out to sea to forage, the other keeps the egg balanced on its feet and tucks it into a brood pouch where it is kept nice and warm. The parents take turns to incubate the egg and after about fifty days a little brown chick breaks through the shell and lets out its first few chirps. The parent on duty feeds the chick every so often by regurgitating stored fish and squid.

During this stage the chick is extremely vulnerable as giant petrels and skuas patrol the colony looking for distracted parents. When a chick reaches an age where it is more capable of fending for itself, both parents go to sea and return every now and then to provision their chick. While their parents are away they gather in large crèches and stand around all day sleeping and whistling. Every so often a chick bursts out in a fit of energy and runs around like mad flapping its flippers and bumping into anything in its path. It's hilarious.

It’s quite remarkable how the parents find their chicks when they return to the colonies. No matter how much they sound the same to us, each parent can recognise the whistle of its chick, and vice versa. The parent lets out a soft cooing sound that can be audible at a great range whilst the chick lets out a three note whistle that varies in amplitude and frequency if it hears its parent. When they finally find each other in the colony the parent lets out a loud polysyllabic trumpeting and to confirm their bond the parent wanders off into the colony while the hungry little chick follows suit, whistling away.

Despite the harsh world in which they live, the king penguin population at Marion Island has been fairly stable over the last few decades and hasn’t shown any signs of rapid decline like many other penguin species have. The last census done during the incubating period estimated a total of 65000 pairs on the island, so counting them this summer is going to be quite interesting.

“A crown is merely a hat that lets the rain in.”

- Frederick the Great of Prussia

"Now let us sing, long live the King."

- William Cowper