On the 9th of August a German owned vessel, the Kiani Satu, was on its way from Cape Town to Gabon when it ran aground in Goukamma Nature Reserve and Marine Protected Area. The 168 m long vessel was carrying 15 000 tons of rice and 330 tons of fuel oil.

Following the event someone remarked: "While there is no current threat to the environment, we hope the ship is towed off soon before this turns into another Seli 1."

Since then oil has been leaking out of the vessel which has washed up on beaches and even entered the Goukamma estuary. The damages to local sandy beach and rocky shore ecological systems are likely to be massive, and already there have been incidences of birds completely covered in oil.

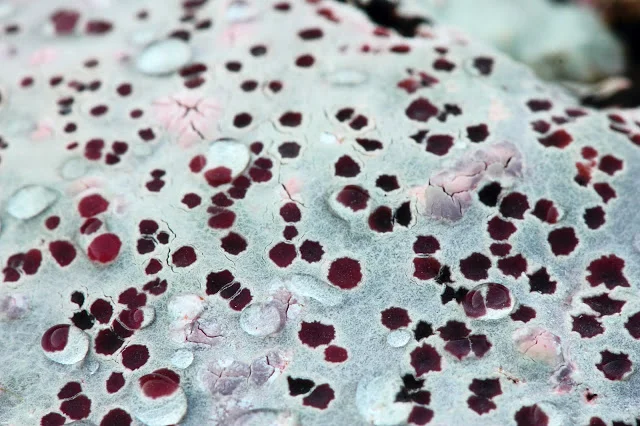

The oil also threatens our valuable estuaries, which are integral to providing refugia for juvenile fish and are also home to the world's only populations of the Knysna seahorse. Unfortunately, oil has already breached the Goukamma estuary and with the swell expected over the next few days, it is possible that the ship will break up further, spilling more oil into the sea. Let's hope that the organisations working around the clock to sort out this problem will be able to reduce the extent of the spill and that the insurance company will cough up to pay all the bills necessary for the clean up operation.