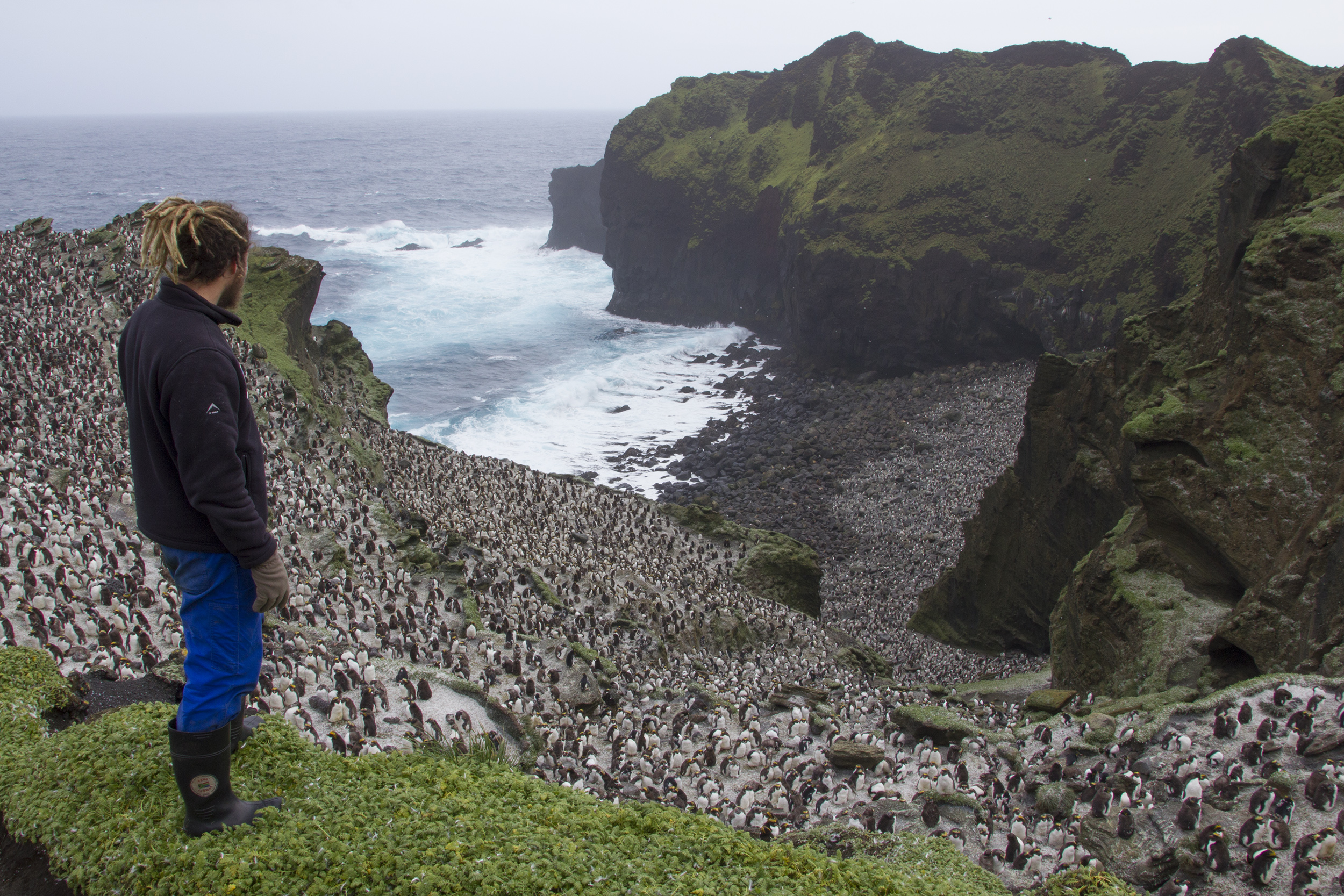

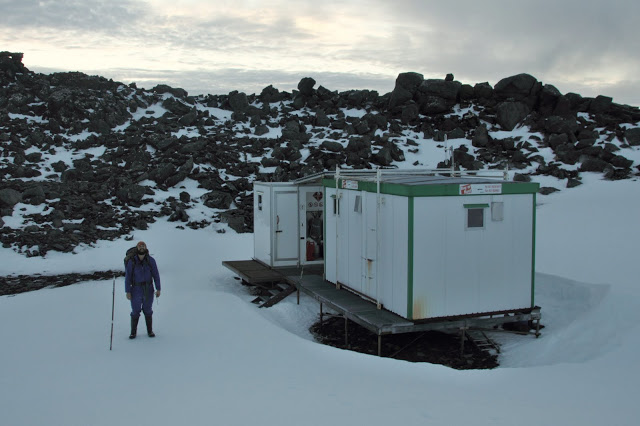

Imagine you are standing on a rock at the edge of the sea, gazing out at the seemingly infinite expanse of ocean that stretches to the horizon. You are hungry, really really hungry. In fact, you haven't eaten for three weeks! Now, jump into that ocean and try find some food. Where would you go? How would you know where you are when you can no longer see land? It's a pretty mindblowing thought to think that there are millions of animals out there that do that all the time. Part of my PhD thesis involves trying to understand how macaroni and rockhopper penguins manage to find food during the resource-limited winter months. During this time they spend six consecutive months at sea, never returning to land.

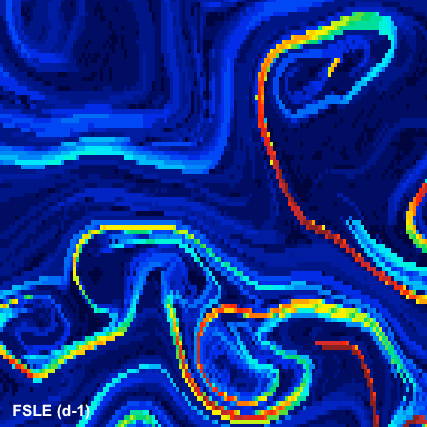

Thanks to satellites and the work of organisations like Aviso, anybody can find out what the ocean was doing anywhere in the world at any given time. For instance, I wanted to find out whether macaroni and rockhopper penguins were using mesoscale eddies and/or submesoscale filaments. These oceanographic processes are known to aggregate and sustain elevated concentrations of zooplankton and fish, and thus act as important foraging areas for many marine predators. Nobody, however, has investigated whether crested penguins utilise these structures during the winter period. The graphic below shows the movements of a macaroni penguin in relation to sea level anomaly (SLA - eddies) and finite-size Lyapunov exponent (FSLE - submesoscale filaments). Notice how the penguin encounters the eddy on May 26th and only leaves on July 21st. That's nearly two months at the same eddy. Also take notice of how the penguin moves in relation to the filaments.