As the tugs pulled the SA Agulhas away from the quayside I waved goodbye to my loved ones and stared out at the vast expanse of sea that lay ahead. ‘I won’t be seeing this place for more than a year!’ I thought to myself, acknowledging the strangeness of such a concept. A few hundred metres out to sea the feeling of adventure had already kicked in, as diving cormorants, porpoising seals, jumping dolphins and a lonesome sunfish filled the calm waters of the cape.

The SA Agulhas isn’t the fastest of ships so the coastline stretching from Camps Bay to Cape Point took all the remaining hours of daylight to pass by, my eyes picking out some familiar spots; the Sentinel near Hout Bay, the BOSS 400 wreck off Sandy Bay, the crayfish factory at Witsands and all those beautiful beaches in the reserve. The last glimpse I shared with civilisation came from the haze of lights emanating from within the arms of False Bay; a lighthouse at the end of each warning ships, like ours, of their extremities. I stared up at the night sky from the upper deck and marvelled at the star studded Milky Way. According to Bill Bryson the Milky Way is one of 140 billion or so other galaxies, many of them even larger than ours. Hmm, space couldn’t be more appropriately named.

The first few days on the ship were rather quiet as most people succumbed to sea sickness and kept to their rooms. I had heard that ginger was a good preventative so I added plenty to my tea and it worked perfectly.

I spent lots of time outside on the deck watching pelagic seabirds gracefully negotiate the crests and troughs of passing swells. These birds feed on small fish and krill near the water’s surface and spend most of their lives at sea, using the wind in their wings and hardly ever needing to flap. The birds weren’t the only ones taking to the air; I was standing at the bow one afternoon and to my amazement saw a fish leap out of the water, spread its silvery wings and glide effortlessly through the air. It was a flying fish! And it was shimmering all kinds of blues and greens. As quickly as it had come, it had disappeared. I stood with my camera in hand and waited eagerly for another one, but to no avail. Staring out at the frigid ocean and its incredible blues I daydreamed, and snapped a few shots of these beautiful birds.

Our expected time of arrival was 08:00 on Sunday, however, we ran into a passing storm and had to change course. The wind picked up and the 10 metre swells made walking down the passages, and breakfast, lunch and suppertime, highly entertaining.

Our new ETA was 03:00 on Monday morning and I was getting anxious. When that morning came I woke up, threw on my fleece and rushed out to the starboard side of the ship. Nothing, it was pitch black. I moved over to the port side and saw the first glimpse of my new home; a few lights emanating from the base. Hmm. I'd have to wait until after breakfast to greet my little piece of sub-Antarctic paradise. When the morning light broke I rushed outside again and there it was. Marion Island, you are so, so beautiful.

We waited on the ship for the helicopter to take us over to the island, but by the time my flight, the last flight, came around there was a problem and we had to remain on board to help pack a few containers. It really didn’t faze me as the SA Agulhas was fast becoming a popular tourist attraction for the king penguins and they were swimming up to the ship in the hundreds to check us out.

The first few days on the island were filled with admin and unpacking, but it was still such a new experience to be in such an incredible research facility (which feels like a space station) and to look out the window and see a completely foreign, but intriguing, landscape. The time eventually came to venture into the field when we were sent to Sealer’s Beach (about 2km north of the base) to deploy GPS loggers on king penguins.

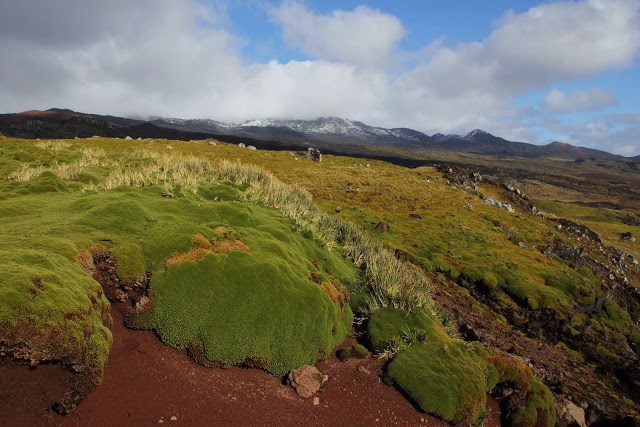

One of the first things I marvelled at was the vegetation. It’s so strange and unlike anything I’ve been exposed to. There are a few familiar grasses and mosses, but then a whole array of plants that I’ve never seen before. There’s

Blechnum

, my new best friend, which is a tiny fern-like plant that is exceptionally nice to lie down on. In the photograph below it shares the landscape with a few mosses and grasses.

There’s

Acaena

, whose leaves are a mix of purples, blues and greens, which gives rise to prickly balls that stick to your clothes. There’s

Azorella

(see below) which forms massive cushions that appear singular or even mossy at first glance but if you look closely they’re actually composed of hundreds of tiny green heads. We have to avoid stepping on them as they can only grow 2 cm a year!

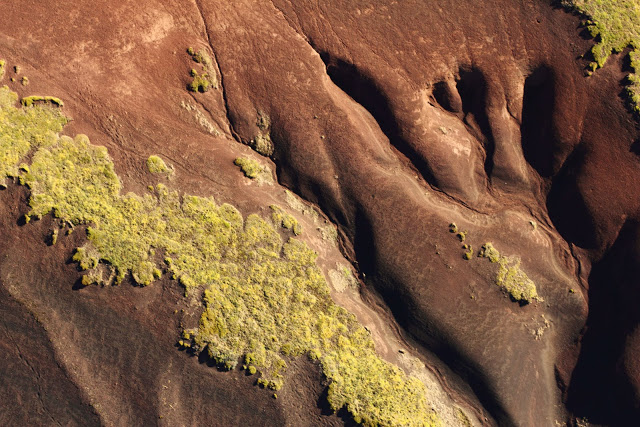

My favourite plant on the island so far is the liverwort

Marchantia berteroana

. Have a look at the photographs below; can you see the circular structures? They're called gemmae cups and are used for asexual reproduction. In the first photograph you'll see that in the one gemmae cup there are two little green things called gemmaes. These get splashed out when it rains, washed down the furrows in the leaf and end up in the ground where they develop into new liverwort plants.

There are also countless species of lichen and a few loving mushrooms.

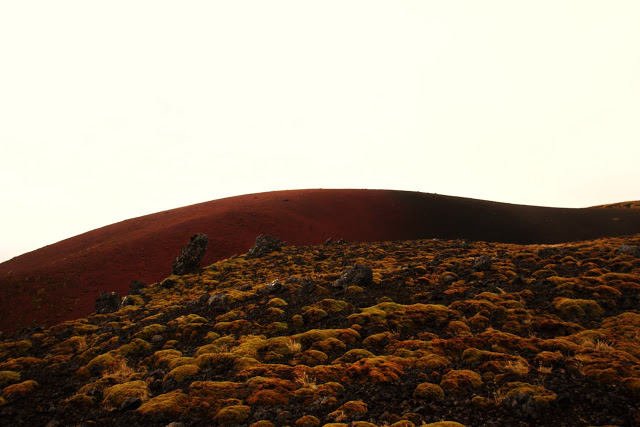

A little bit of Marion Island history… Once upon a time there was an island, and once upon a time there wasn’t. Marion Island hasn’t always been around, as the very waters in which it lies now used to be an open ocean of crests and troughs. It started off as a small little volcanic cone oozing lava out onto the seafloor some 5000 metres below the sea surface. Gradually it grew and it grew until it popped its volcanic head out into the aerobic world about one million years ago. It caught the attention of passers-by, such as seals and seabirds, which were quick to colonise the coastal regions. Plants soon followed as seeds and spores arrived from the west via the wind or attached to seabirds. Those that could survive the harsh climate flourished, while those that couldn’t, perished. Over time the island has changed its face many times over but today it stands at 1230 metres high and covers almost 300 square kilometres.

There are 28 species of bird on the island. One of the most studied birds are the wandering albatrosses (in the first two photographs below) which exhibit incredible mating dances. In the first photograph a young female practises with an adult male so that by the time the next breeding season comes she'll be on top form to impress her partner. The other birds featured below are as follows: black-faced sheathbill, rockhopper penguin, greyheaded albatross and sooty albatross.

There are three species of seal on the island; the Antarctic and sub-Antarctic fur seal, and the elephant seal. Another major marine mammal is the killer whale, of which there is a large group that regularly patrol the waters around the base. I saw my first killer whale the other day and couldn't believe my eyes! Such incredible creatures.

In the first week on the island the previous team’s birders took Marguerite and I around the island to introduce us to all her beautiful nooks and crannies and briefed us on what the work entails. There are nine little huts stationed around the island and we stayed at seven of them, each for a night. One thing that is especially weird about walking around Marion Island is that every footstep sinks at least a few centimetres into the ground. It’s just so wet and mushy! People often fall into mires, which are extremely wet patches, and lose a gumboot.

The round island took us eight days, during which we had relatively good weather. The only exception was on our second to last day where we had to climb Karookoppie in a gusting 100 km/hour wind coupled with icy rain. Nightmare! Each day on Marion is determined by the weather. The same walk could either be incredible or miserable, depending on the conditions. The weather’s also very temperamental. It could be a calm and blue-skied day, beautiful to begin with, and a few moments later a few clouds roll in and suddenly it’s bucketing sideways. On the colder days the raindrops turn into ice pellets, which deliver quite a sting. On most days it only snows up at the main peaks and not at the coast, however, in the winter months the entire landscape is regularly covered in a thick, white blanket of snow.

Marion Island is still an active volcano, although the last activity was recorded in 1980 when there was a lava flow on the west side of the island.

All in all, my experience of Marion Island so far has been surreal. This sub-Antarctic island, with its plethora of life, is just so beautiful, and so otherworldly, that it’s been hard to take it all in. I’ve tried and tried to describe what I see and feel but I’ll never truly capture the essence of this place simply because it is indescribable. It is wilderness in its rawest form and I am so privileged to be here.