A tranquil pitter patter swirled down from the ceiling and licked at my eardrums. On the window in front of me a hundred or so little droplets cascaded steadily downwards as I watched them with simplicity. I watched how they would sometimes reach out to each other in moments of stillness and upon touching would scurry off with gravity. I watched how as the wind blew, their movements would shift in a jagged synchronicity, catapulting them in unison across the glass. I looked past them and saw the ocean explode into the sky.

‘It’s wild out there’ I thought, turning my eyes on a frigid sea saturated with mountainous swells. I watched as an icy blue crest unfurled an angry lip and crashed into the shallows, turning everything white. The surge launched up the volcanic rock-face of the shore and scattered a vast white blanket over the sky. It lingered, suspended momentarily as if each droplet had wings. Then it fell gently and the droplets returned to a sense of peace and place, filtering back into the ground or wallowing in a rock pool. I thought about how water is constantly on the move. But then I was quick to remember a watery state frozen in time: ice, and its many forms.

A few weeks ago I woke up one morning and opened my blinds. It was a Sunday and it was appropriately sunny. The blue sky made for an eye-indulging contrast to a landscape carpeted in snow and the grasses were hushed and sitting still; there was no wind. ‘A perfect day to explore the ice plateau’, I thought, and rushed outside to gaze inland. The peaks were silhouetted against a clear sky and it was all too perfect. I quickly packed my backpack and Johan and I set off into the heart of this wintery wonderland.

Looking around I was amazed at how the snowfall had completely transformed the landscape. It was unbelievable. I kept trying to find new adjectives to describe its epicness and constantly found myself muttering ‘It’s amazing.’ I’m always fascinated with how wilderness has the ability to astound and confound, leaving one sedated by awe. It’s that vast nothingness that symbolises everything. It encompasses all that is wild and untouched, tranquil and perfect. Each step was done so with a smile, gradually edging closer to Katedraal Hut. I kept on thinking to myself: ‘Here I am, on a volcanic island in the middle of the Southern Ocean, more than two thousand kilometres away from any civilisation, and I’m wading through this surrealistic, snow-carpeted wilderness in a T-shirt as sunshine streams down from a blue sky.’ Never in my wildest dreams.

The wind had sculpted beautiful snow dunes with ripples as you’d find on the bottom of a still lake or calm beach. The sun was low and the snow sparkled in its angular presence. As it set, the sky was gradually coloured in layer by layer, with a deep blue closest to the stars and a rosebud pink softening the billowy clouds on the horizon. A sliver of moon smiled and so did I, this landscape was contagious.

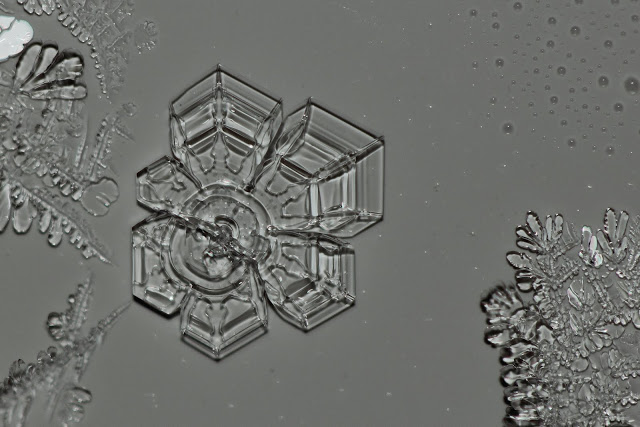

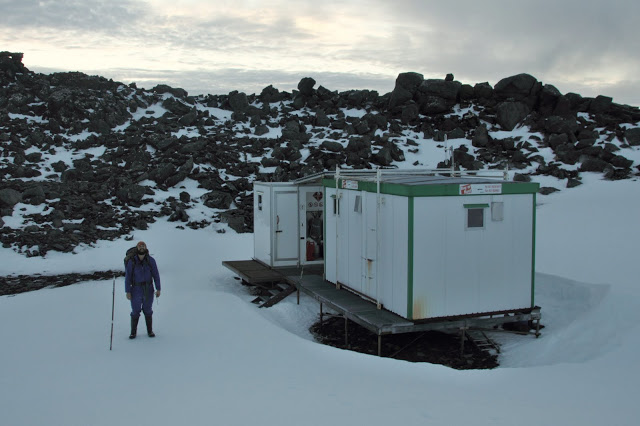

When we reached the hut we found that some snow had forced its way inside through gaps in the door and air vents, the water in the kettle was completely frozen, the floor of the pantry was an ice rink and the walls were covered in the most beautiful ice crystals. 'It gets seriously cold up here!' I remember thinking. We soon got to work turning the kettle ice into hot chocolate, put on the heater, and enjoyed an awesome evening in Marion’s icy attic.

The winds picked up just after midnight and howled as they swept past the hut walls, giving it a little shake as if to remind us of its authority up here. I got up and went outside to pee, trying not to get blown away. The skies were clear and the stars were bright. Being so far away from the masses of artificial light and smog-suffocated cities, it was a perfect opportunity to capture the stars; so I whipped out my camera and tripod, tied on a piece of string and a pen to keep the shutter open, and let it capture their circular ways. I went back to sleep holding thumbs that the weather gods were in a generous mood and would give us another beaut of a day.

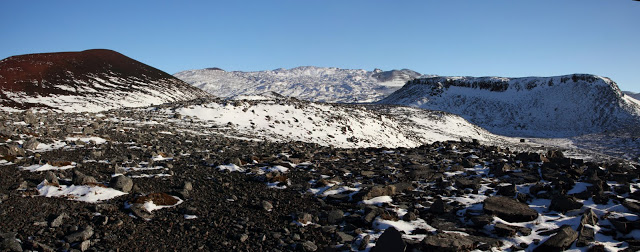

We got our wish and left early to explore the ice plateau. Once again the landscape’s rawness etched smiles all the way up our cheeks and froze them there. The skies were clear, the air was calm and the sun glistened off the icy terrain at low angles. The landscape was so frozen that at times it made walking nearly impossible, so we often indulged in a more entertaining form of locomotion:

.

We climbed up one of the highest peaks on the island, had tuna mayonnaise with provitas and admired the view, with the highest, Mascarin (1231m), just a well-flung snowball away.

Fast forward a few weeks later and I found myself riding that snowball over to Mascarin Peak. To time travel one last time, I’m going to rewind two days back to a Saturday. Saturday’s weather forecast was wind and rain, Sunday’s wind and rain, and Monday’s partly cloudy, a little wind and no rain. It was the day of the high pressure system; a very good thing in this part of the world. On the Saturday I was to count nesting gentoo penguins at several colonies on the way to Kildalkey Hut and meet up with Christiaan, who was counting elephant seals, before heading over Karookop to Greyheaded Hut. As predicted the wind and rain followed us all the way to Greyheaded. The plan for the next day, high pressure Monday, was to head up Greyheaded ridge and into the interior, climb up Mascarin Peak, and head over to Katedraal for the night before our descent to base the following day. Good weather was essential and after two long days of howling wind and rain we were sceptical that such a wish would be granted. The winds picked up in the late evening and the hut rattled and rocked into the early hours of the morning.

We awoke early and were quickly enveloped in excitement. The wind had dropped and atop a mist-shrouded valley lay a majestic Mascarin, glistening magically in the early morning sun.

We knew it was going to be an epic hike so we left while the air was still ripe with the birth of the day and headed up Greyheaded ridge to Pyroxene Kop.

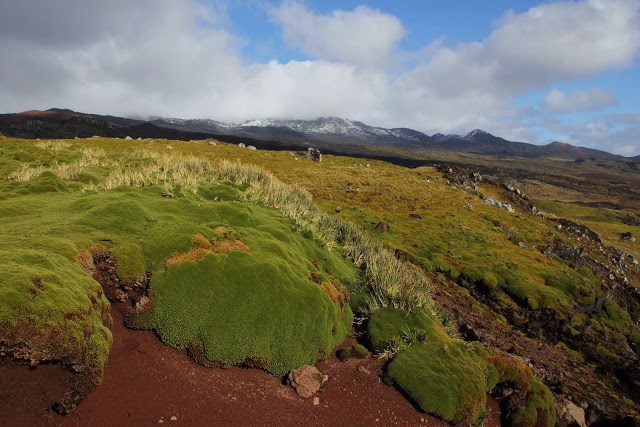

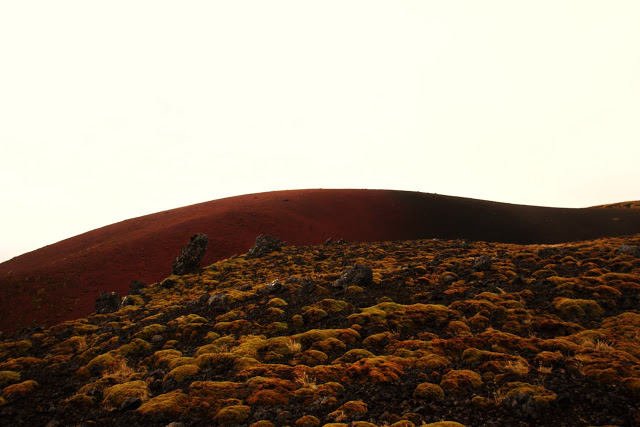

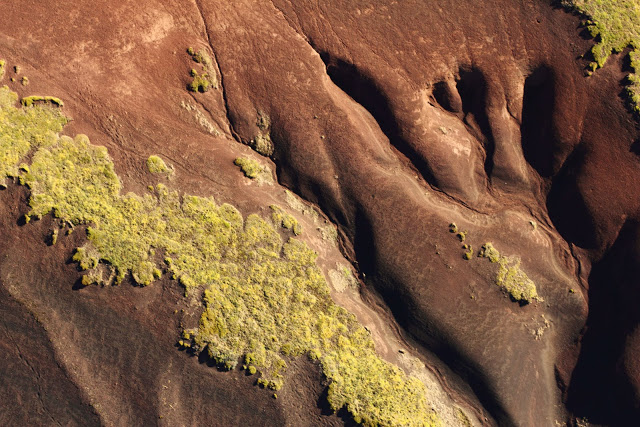

After a while the mist in the valley started to clear and the interior was looking amazing. We gleefully waltzed across and up the Basalt Gordyn (every now and then sending an ecstatic 'Whooooooweeeeeeee!' echoing through the valley) and found firm footing on compact snow and black lava coated in mosses and lichenicolous fungi.

The snow eventually started getting really icy and rather slippery, so we strapped some trusty crampons to our boots and continued up through a magnificent landscape strewn with dips and ridges of ice and snow.

By the time we reached West Peak we were blown away by the interior’s surreal nature (and not by the wind, which was still non-existent). Frozen hills and jagged outcrops of horizontal icicles seduced one's eyes into exploring every little detail of the landscape while little puffs of cloud danced in the warm glow of a smiling sun.

We marched on, negotiated a few icy slopes and headed up Mascarin. At 1231m on a perfectly clear, wind-still day, it was an unbelievable place from which to admire this frozen paradise, kept raw and isolated by its volcanic heart and wild nature. Surreal man, surreal.

On the way to Katedraal we passed the ice caves near Resolution Peak which were completely snowed over, testament to the landscape's wintery extreme. An incredible evening sky and a few bits of random commentary and wild cries entertained our minds as our bodies languidly strolled onwards, keen to collapse into the arms of our next abode.

On arrival we found the water tank buried deep in the snow and inside the hut the usual frozen kettle and piles of snow greeted us with a frigid embrace. We warmed up by baking a chocolate cake in celebration of Christiaan's upcoming birthday and then retired to the comfort of our sleeping bags to reflect on the remarkably outlandish and surreal adventure we had just had. Outside the night air was completely still and the silence remarkable. Such tranquility, so much zen. I closed my eyes and let my mind wander. Was it all a dream? It certainly could've been.